We have a guest post today from club member Tim Spanton.

Tim has kindly provided a fascinating bit of analysis from his own chess blog on a game he played for us in the Central London League.

Here it is:

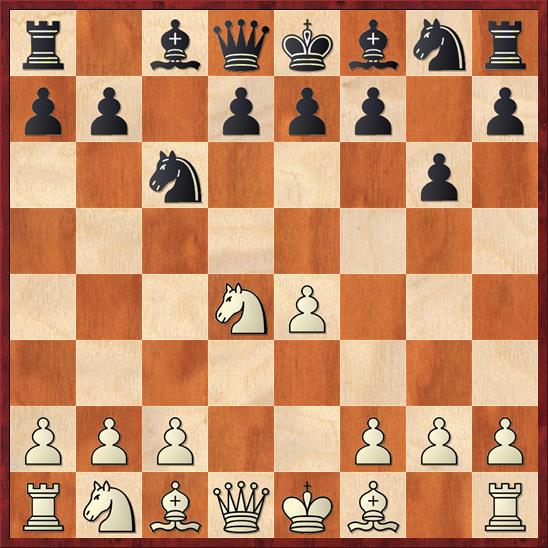

Before this month, the position after 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 had occurred 70 times in my games.

White has tried numerous continuations, but overwhelmingly most popular are 5.Nc3 and 5.c4

Just one of those 70 games saw White playing 5.Nxc6!?

This month, the diagrammed position has, so far, occurred twice in my games, and in both of those White played 5.Nxc6!?

It is the type of move books often warn against in the Sicilian, as the recapture 5…bxc6 strengthens Black’s centre.

But you might be surprised, as I was, to learn it has a respectable pedigree, having been a favourite in simuls of Pillsbury.

Lasker used it to beat Bird in their 1892 match, and it was also played by Albin, Blackburne, Schlechter and von Bardeleben.

In more modern times it was occasionally the choice of Mikenas, Yanofsky, Pilnik, Szabo, Alburt and Beliavsky.

So the move has a respectable history, which leads me to ask the question: Revival or Coincidence?

In other words, has 5.Nxc6!? taken on a new lease of life, perhaps as the result of being recommended in a book, in a magazine or online? Or do my two recent experiences just add up to a statistical freak?

After 5…bxc6, by far the commonest continuation is 6.Qd4, and this was indeed played against me when I first met the line 13 years ago.

But analysis engines tend not to be particularly impressed by this move, which struggles to get into Stockfish9’s top ten choices.

Instead, Stockfish9 likes 6.Nc3 and 6.Bc4.

The former was played against me at a tournament earlier this month in Bamberg, Bavaria, and the game was effectively over inside 10 moves.

Daniel Wiemann (1591) – Spanton (1878) continued: 6…Bg7 7.Be3 d6 8.Qd2 Qa5 I had no intention of playing …Bxc3, but I hoped the threat might induce Black to interrupt his natural plan of development. 9.Bd3 Rb8 I now expected 10.Nd1. Instead there came catastrophic loss of material: 10.Qc1?? Rb2 11.Bd2 Bxc3 12.Qxb2 Bxb2 (0-1, 38 moves).

The move 6.Bc4 was played against me in a Central London League match on Thursday.

Matthew JD Baker (148ECF) – Spanton (163ECF) continued: 6…Bg7 7.0-0 7.Qf3 was played at least twice by Bellon Lopez. One point is that after 7…Nf6, White can try 8.e5!? (Bellon Lopez, in the two games featured in ChessBase’s 2018 Mega database, once chose 8.0-0 and the other time plumped for 8.Nc3) as 8…Qa5+ does not win the e5 pawn, since White has 9.Qc3. 7…d6 8.Nc3 Nf6!? More solid was 8…Qc7. 9.Qe2 Black has a comfortable game after this. More challenging was 9.e5 dxe5 10.Qxd8+ Kxd8 11.Re1 (not 11.Bxf7?? as the bishop is trapped by 11…e6), when White will recover his pawn, leaving a position in which Black has the only central pawn, but also has two isolated queenside pawns. 9…0-0 10.Rb1 Qb6 Threatening a nasty skewer with 11…Bg4. 11.h3 a5 12.a4?! This is a little weakening. Stockfish9 reckons the game is even after 12.Rb1 a4 13.Be3. 12…Ba6 12…Nd7 was probably even stronger. 13.Bxa6 Qxa6 14.Qxa6 Rxa6 My main analysis engines, Stockfish 9 and Komodo 9, reckon the position is equal, but it is easier for Black to play, thanks to having the simple plan of queenside pressure (0-1, 39 moves).

So, revival or coincidence?

My verdict (for now): Coincidence, but watch this space.