It was the year 1890. Preston had won the league, the “Elephant Man” Joseph Merrick died and, closer to home, Battersea Bridge opened.

It was also the year a fully-paid up and active Battersea member, who lived nearby, challenged for the world title.

In a newly re-discovered newspaper clipping, we have found evidence that in 1890, Battersea had the second strongest player in the world after the domineering titan of chess Wilhelm Steinitz.

Isidor Gunsberg, a strangely neglected figure in chess history, was one of the best players of his generation, which included Mikhail Chigorin, Henry Bird and Joseph Blackburne – all of whom he beat in matches – not to mention Johannes Zukertort and a young Emanuel Lasker.

Gunsberg was also one of the most prolific chess journalists in the Victorian and Edwardian ages, having columns in a number of national publications.

Members of Battersea always knew the Hungarian-born naturalised Brit had visited the club. One long-serving stalwart even joked with me the other night that he’d played Gunsberg. He hadn’t, he’s not that long-serving.

But whether Gunsberg was ever actually a member, and if so when he may have become a member, was unclear because there is precious little written down about him.

Gunsberg (1854-1930) never won the club championship and only appears as a fleeting mention in the official club history Fifty Years of Chess at Battersea by L.C. Birch.

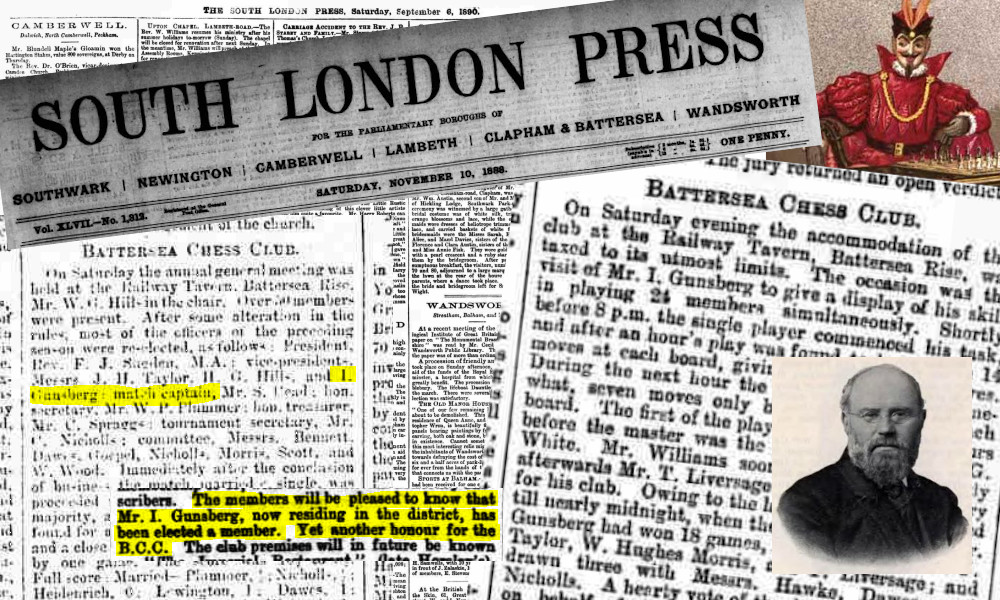

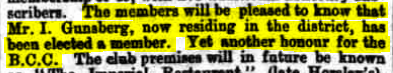

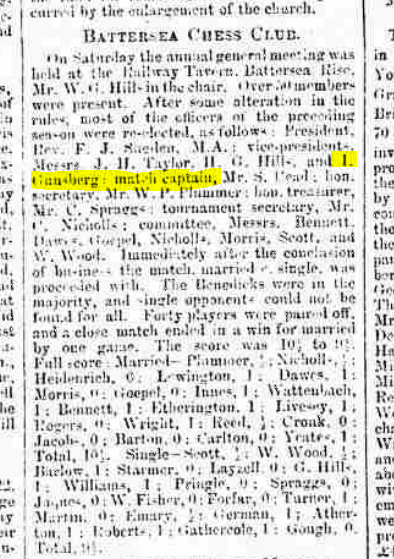

But now, thanks to a report of the club’s 1890 annual general meeting unearthed in the South London Press, we can confirm he became a member and pinpoint exactly when.

‘Yet another honour for Battersea’ – South London Press, 1890

The twice-weekly “SLP”, which Your Correspondent and another current member, Chris Beckett, once worked for, reported on September 6, 1890, that Gunsberg had been elected a member of Battersea. It said he was “now residing in the district”.

And that’s not all. Gunsberg, according to a report two months later in the Morning Post, this bastion of Battersea was on the committee as “vice-chair”:

Subs at the time were 3s, compared to £60 today, to cover the rent for the club’s new venue in Horsley’s Restaurant, Clapham Junction. In 1889 it was recorded the club had 44 members, including 18 new that year, and 46 in 1890 when Horsley’s on Lavender Hill had a new owner and was renamed the Imperial Restaurant. By the mid-1890s the club was nearly 100-strong.

That places Gunsberg with us right at the peak of his powers just in the year he drew the match against Chigorin in Havana which effectively convinced Steinitz, and himself, that he was now a worthy challenger for the world title.

It also ties together the question of why a Battersea member named W. Williams penned this stirring acrostic which, according to the chesshistory.com, was published on page 275 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, November 28, 1890:

For Williams, his “bravest Knight” represented not just “Merrie England”, but Battersea.

The Steinitz match, which Gunsberg eventually lost, started three months after he joined and was close: Gunsberg went down with a score of four wins, six losses, and nine draws.

That year Battersea won the Junior Metropolitan Chess Club Trophy (value £6) at the first time asking. But a year later, according to the Morning Post, the club lodged a protest.

Battersea Chess Club is not alone in understating Gunsberg’s part in history. In his book Eminent Victorian Chess Players, Dr Tim Harding describes him as “the most neglected major figure in British chess”.

Indeed, if you ask most chess fans which Brits have challenged for the world title, most will say Nigel Short in 1993 and Howard Staunton. But they will probably add that Staunton is technically a red herring because you can’t really count him as, while he may have been the best in the world, “world champions” didn’t exist before Steinitz. Few will come up with the name of Isidor Gunsberg.

So, it seems, this erstwhile Battersea member has been relegated to being the answer to a tricky pub quiz question.

So why has one of the greatest names in British chess history been forgotten? His story is, in fact, fascinating.

Early in his chess career, Gunsberg had been the main operator of the chess-playing automaton Mephisto, built in 1876 by Charles Godfrey Gumpel at his home in Leicester Square.

Unlike “The Turk”, which was a con trick, Mephisto had no hidden operator and worked electromechanically. It was quite bizarre. The machine consisted of a life-size figure of an elegant devil, with one foot rendered as a cloven hoof, dressed in red velvet and seated in an armchair in front of an unenclosed, open-sided table.

In 1879 Mephisto, with Gunsberg manning the controls, went on tour, defeating every male player. When playing ladies, however, Mephisto would first obtain a winning position before losing the game then courteously offer to shake their hand afterward.

Gunsberg first came to Britain in 1863, aged nine, and lived here on and off before spending his whole adult life, apart from his chess travels, in the UK. But for some reason, this son of a Jewish merchant and Russian-born mother was only granted citizenship in 1908.

In 1879 Gunsberg married his first wife Jane and gave his address as 35 Rose Hill Terrace, Wandsworth. He probably meant Rosehill Road, near the flyover.

In the 1881 census, Gunsberg appears as a married man living in Mile End Road in Stepney, which was a popular destination for Jewish immigrants at the time.

By the 1891 census, he had moved back south of the river to Battersea and was listed as a “chessplayer and journalist” living with his wife with whom he had three children. In total, they had six but three died in infancy.

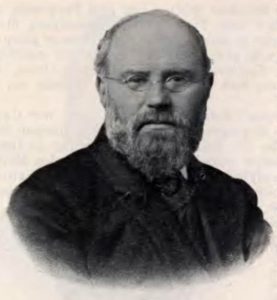

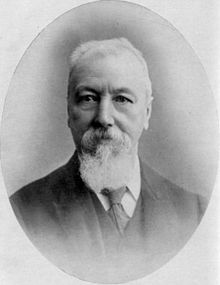

Isidor Gunsberg: After his defeat

However, in May of 1891, Jane also died, leaving Gunsberg with a young family to care for. It is not known how much of an active father Gunsberg became, but he never played a serious match again.

Gunsberg remained a member of Battersea and, just four months after his wife’s death, the official club history recorded him holding a simul in Battersea’s new venue, The Railway Tavern, which is now called The Hawkins Forge.

That event was also reported on in the South London Press edition of September 26 as a “display of skill” against 24 opponents:

So Gunsberg was a member, but did he actually play for the club?

Aged 40, he is referred to again in 1894 in another South London Press report as being present at the club’s annual general meeting seemingly with the title “match captain”.

By then Gunsberg made a living through visiting other clubs to hold simuls and his chess writing. He took up a number of columns which later included The Daily Telegraph.

In British Chess Literature to 1914: A Handbook for Historians, Harding lists a string of Gunsberg’s contributions – he had a lot – and describes him as “probably the most prolific chess editor of the Victorian and Edwardian eras”.

In May 1893 Gunsberg married his second wife Miriam, who was a chess journalist herself.

He played Hastings in 1895, but never recovered his former strength.

1881 census: Isidor Gunsberg. Age: 26. Born in Budapest, Hungary. Address: 287 Mile End Road (Hamlet), London. Occupation: Tobacconist and professional chessplayer. Married to Jane Gunsberg (age 28).

1891 census: Isador [sic] Gunsberg. Age: 36. Born in Hungary. Address: 22 C … [illegible] Road, Battersea, London. Occupation: Chessplayer and journalist. Married to Jane Gunsberg (age 38). Children: Alfred Gunsberg (son, age 6), Bertie Gunsberg (son, age 5), Lionel Gunsberg (son, age 3). One servant was a member of the household: Alice Jennings (age 21).

1901 census: Isidor Arthur Gunsberg. Age: 46. Born in Hungary. Address: 113 Clifford Road, Monken Hadley. Occupation: Author, journalist. Married to Agnes Jane Gunsberg (age 38). Children: Alfred Tudor Gunsberg (son, age 17), Kathleen Ramage Gunsberg (daughter, age 2 months), Miriam Gunsberg (daughter, age 4), Winifred Grace Gunsberg (daughter, age 6). One servant (Elizabeth Hatfield, age 56) and one relative (Winifred Ramage, age 27) were members of the household.

How Gunsberg appears in census entries

Our friends over at Streatham & Brixton Chess Club, who also have a connection to Gunsberg, have researched the player’s movements and noted several addresses where he resided around south London.

They include 19 Deronda Road near Tulse Hill and Knollys Road in Streatham.

‘Our champion now across the seas […]’

But Gunsberg’s defining moment was undoubtedly his 1890-1 match with Steinitz.

By then Gunsberg was already established as one of the strongest chessplayers in the world.

He beat Henry Bird in 1886 and his friend Joseph Henry Blackburne, who also lived in south London, in 1887 in challenge matches.

Gunsberg also had a string of tournament successes in the 1880s that included first at Hamburg 1885, shared first with Amos Burn at London 1887, first at Bradford 1888, and shared first with Bird at London 1889.

In early 1890 he had drawn a match in Havana against the great Chigorin which convinced him it was time to challenge Steinitz.

New York’s Manhattan Chess Club brokered the negotiation initially and Steinitz, the overwhelming favourite, settled in principle to play for a stake of $1,500. Adjusting for inflation, that works out at around $42,000.

Conditions were agreed upon on December 6, 1890. The winner would be first to 10 games (draws not counting), or most wins after 20 games. A draw would be declared in the case of nine wins each.

‘Go, gallant Gunsberg!’

The winner would receive the sum of $1,000. Gunsberg received $150 traveling expenses from the Manhattan Chess Club. The winner of each game received $20, the loser $10 and in case of a draw, they both got $10.

British amateurs contributed £75 towards Gunsberg’s share of the prize fund. Could fellow members of Battersea have been among them?

Here is chessgames.com’s account of the match:

Steinitz took an early lead with a win in game 2 but the match was suspended after game 4 because Steinitz had a bad cold.

In game 5 Steinitz lost with the white pieces in a Queen’s Gambit, after which he vowed to keep playing this opening until he won with it.

With Gunsberg pulling ahead, interest in the match increased. Still not fully recovered from his cold, Steinitz managed to win game 6. During this game, Gunsberg exceeded the time limit but Steinitz refused to claim a win. Steinitz reached his goal of winning with the Queen’s gambit in game 7 and retained the lead for the rest of the match. After a brief Christmas break, Gunsberg struck in game 12 with the Evans Gambit.

Prior to the match, Steinitz had challenged Gunsberg to a theoretical duel in this opening. The contested position had also previously arisen in the adjourned Steinitz-Chigorin cable match and the public had been looking forward to Gunsberg taking up Steinitz’s challenge. Steinitz did not show up for game 18. The telegram he had sent to excuse himself had been delayed. Gunsberg could have claimed the game but did not. Gunsberg played the Evans Gambit for the 4th time in game 18. Gunsberg had previously scored well with it, but he lost this game.

Steinitz drew game 19, thereby winning the match and retaining his title (+6 -4 =9).

Description taken from chessgames.com

Gunsberg, who would undoubtedly have been a Grandmaster if the title had existed then, had failed. Yet he came far nearer to winning than anyone expected.

Two years after their match ended, Steinitz, it seems, had rather a low opinion of his opponent.

In a July 1893 issue of Emanuel Lasker’s magazine the London Chess Fortnightly quoted these remarks about Gunsberg by Steinitz:

“Mr Gunsberg is not alone a chess professor, but he also professes to be a philosopher of the so-called ‘individualistic school’, and he has lectured and written on doctrines which, if I may quote myself, are based on the theory that ‘one man has rights, but two men have none’. When, however, he applies his egoistic principles to chess affairs, he finds that though he may be unique in the chess world he is not alone in it. For instance, he seems to be possessed of the idea that the championship of the world can only be at stake when he himself is a party in a contest. Thus he played a match with Chigorin for ‘the championship of the world’, and the whole chess world laughed. He fought another for the title against myself in which he virtually received the odds of the draw and played to take advantage of the odds. The whole chess world might have laughed if – he had won it …”

Extract from London Chess Fortnightly taken from chesshistory.com

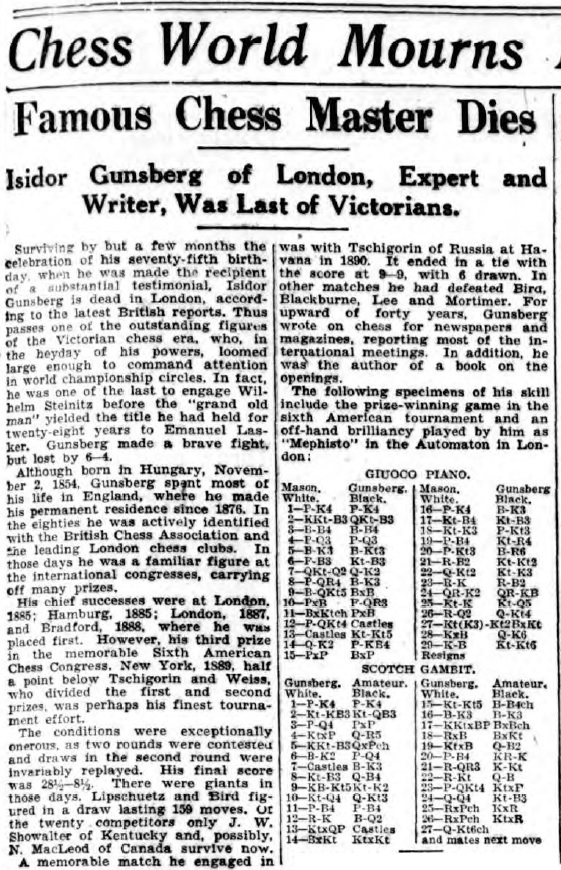

Isidor Gunsberg died bankrupt on May 2, 1930. His death was reported around the world, including this obituary in a New York paper called The Sun.

Gunsberg was buried in a pauper’s grave in Streatham Park Cemetery. Today the grave is unmarked, according to the Streatham & Brixton Chess Blog which tracked it down to the precise location of plot 8478, in square 6.

Meanwhile, the great Steinitz, who was succeeded as world champion by Lasker and died in 1900, has a grand edifice bearing his name at the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn, New York.

Battersea Chess Club has played host to some illustrious names in its 135-year history.

Among them are the first women’s world champion Vera Menchik and Raymond Keene, who narrowly lost out in the race to become the first UK-born Grandmaster.

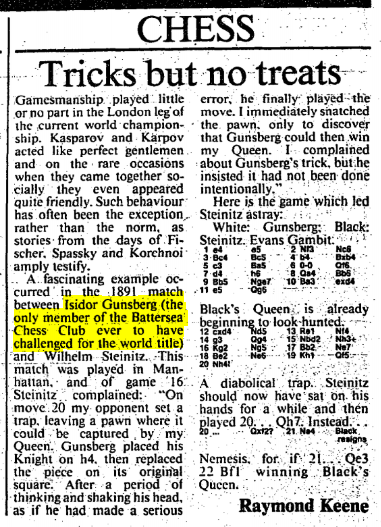

A closer examination of newspaper clippings has revealed Keene, another prolific chess columnist until this year, wrote about our little discovery in his column in The Times, September 13, 1986.

He described Gunsberg as “the only member of Battersea Chess Club to have ever challenged for the world title”. However, I am not sure if I had presented the below article as evidence it would have been accepted as conclusive.

More recently, GM David Howell, who has at times this year occupied the England number 1 spot, is another strong player – super-strong, in fact – who has played for the club.

And guess what? He is also now a chess columnist, writing the Saturday column in The Times and replacing Keene in The Sunday Times.

But Isidor Gunsberg, who like Keene came so near but so far from a major place in chess history, is the pick of the lot.

He remains to this day one of only two Brits ever to vie for the title of official world champion.

Surely, taking that into account, he must be the strongest player ever to play for the club?

Acknowledgments

I have relied heavily for “facts” here on the excellent, but now hibernating, Streatham & Brixton Chess Blog while researching Isidor Gunsberg. I really hope it will restart. The South London Press, of course, is the smoking-gun source and also the Morning Post, both found in The British Newspaper Archive. Two books by the chess historian Dr Tim Harding were borrowed from for background. They are Eminent Victorian Chess Players (2012) and British Chess Literature to 1914: A Handbook for Historians.

Joe Skielnik was also a useful fount of knowledge and pointed me to several other sources, including chesshistory.com, chessentials.com, and zanchess.wordpress.com.